There is no extent information about Ernest Dewley’s birth place, birth date, parents, education level, or type of work.

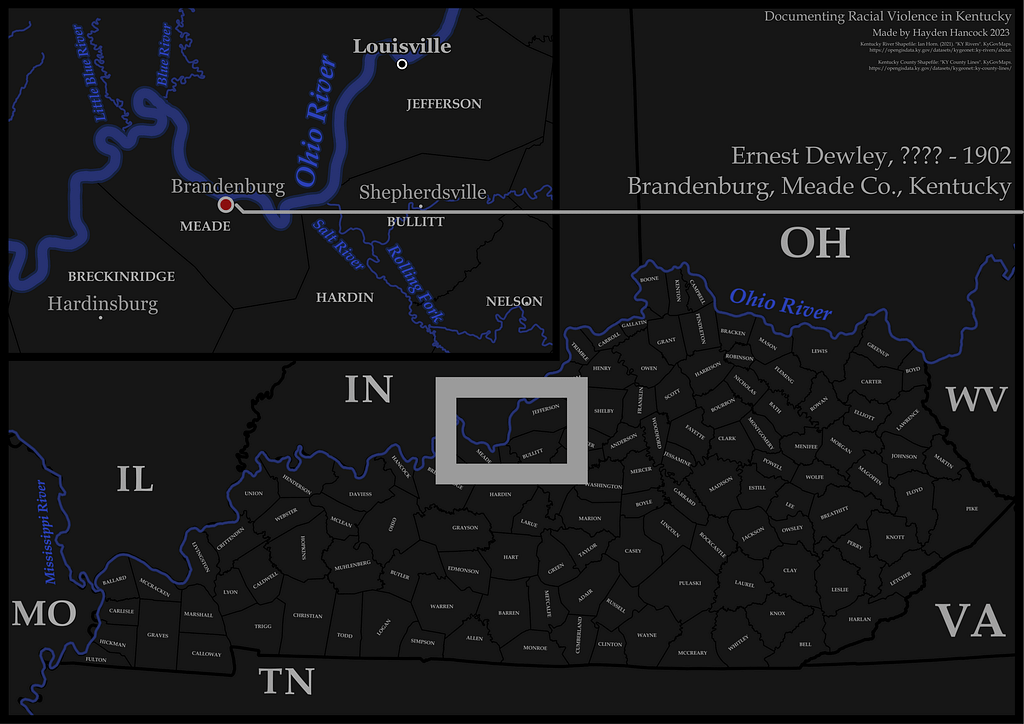

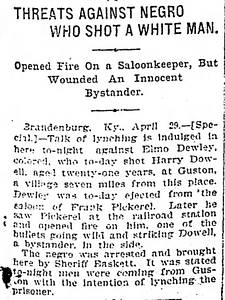

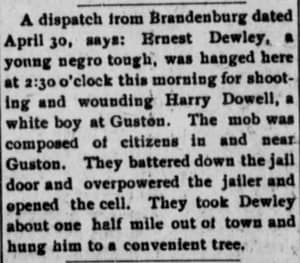

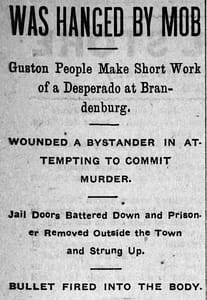

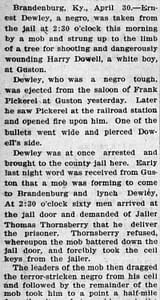

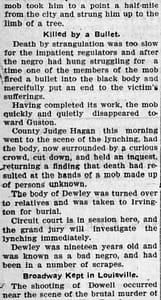

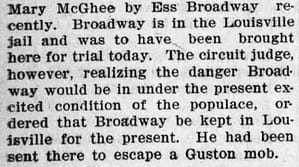

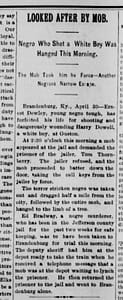

Ernest Dewley was visiting a saloon on April 29th, 1902 in Brandenburg. He was kicked out by Frank Pickerel, the owner of a saloon for known reasons. Later that day, Dewley tried to shoot Pickerel at the railroad station. The shot went wide and hit a bystander, Henry Dowell, a young white man. Dewley was immediately arrested and taken to county jail in Bradenburg. In Guston, a mob of sixty men assembled and broke into the jail around 2:30 am, taking the keys from the uncooperative jailer Thomas Thornsberry. They dragged Dewley about half a mile into the county, where they hung him on a tree. However, he was actually killed by one of the mob shooting him while he was still being strangled. According to “The Twice-a-Week Messenger,” Dewley was 19 when he died. The next day, Judge Hagan visited the site, held an inquest, and determined that Dewley was killed by a mob of persons unknown. Dewley’s body was given to relatives and was taken to be buried in Irvington.

The lynching of Ernest Dewley reveals the role newspapers played in promoting lynching by casting the victim in a negative light. The Owensboro Twice-A-Week Messenger described Dewley as a “desperado” who “…was known as a bad negro, and had been in a number of scrapes.” The Louisville Courier-Journal spread rumors of a lynch mob forming in Brandenburg and that it was headed to the jail to lynch Dewley. After the lynching, the Paducah Sun stated that Dewley had been “looked after,” or rightfully dispatched, by the mob. The newspapers did not frame the lynching of Dewley as an unlawful kidnapping and murder of a state prisoner, though all the newspapers reported that the mob broke into the jail and overpowered the jailer. Thus, many newspapers contributed to the idea that lynchings were a necessary part of law enforcement and an acceptable part of racial segregation.

Location of the Lynching